Goals

After reading this section of notes, you should

- have a greater appreciation for the application of the phase-plane methods covered in notes 11 and notes 12 in biomathematics.

Background

Mathematical models for biological systems often involve interacting variables. Such models take the form of a coupled system of nonlinear (typically autonomous) differential equations. When the system is of size two, phase-plane methods can be exploited to obtain information about the biological system being modeled. Even for higher-dimensional systems, phase-plane methods may still be useful and make it easier for us to understand what goes on in fairly complicated mathematical models.

In this section of notes, we will apply our phase-plane methods to analyze three models. We begin with a simple model for the populations of interacting species, then consider a variation on the general competition model we briefly introduced in our discussion of compartment models. Finally, we analyze the chemostat model for the nutrient limited growth of a bacterial cell population.

A Simple Two-Species Population Model

Consider the system

dxdt=(3−x)x−2xy=x(3−x−2y)dydt=(2−y)y−xy=y(2−x−y)

Equilibrium points

Equilibrium points for the system satisfy

0=x(3−x−2y)0=y(2−x−y)

(x∗,y∗)=(0,0)

(x∗,y∗)=(0,2)

(x∗,y∗)=(3,0)

(x∗,y∗)=(1,1)

are equilibrium points. In the context of the population model, the equilibrium point (1,1) is called the coexistence steady-state because in all of the other three equilibrium points at least one species dies out.

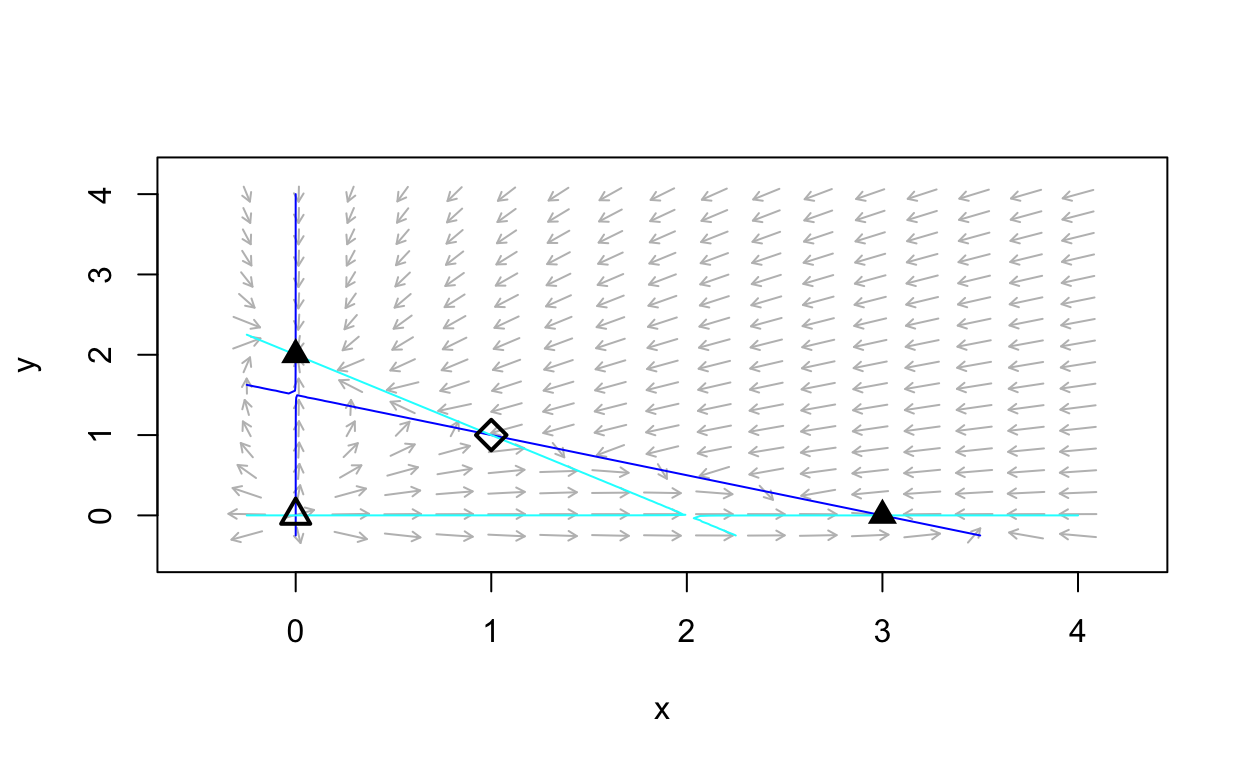

Let’s confirm our equilibrium values by plotting the nullclines for the system.

Show code

simple_pop <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[1]*(3-state[1]-2*state[2])

dy <- state[2]*(2-state[1]-state[2])

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(simple_pop ,

xlim = c(-0.25, 4),

ylim = c(-0.25, 4),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(simple_pop,

xlim = c(-0.25, 4),

ylim = c(-0.25, 4),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(simple_pop, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq2 <- findEquilibrium(simple_pop, y0 = c(0,2),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq3 <- findEquilibrium(simple_pop, y0 = c(3,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq4 <- findEquilibrium(simple_pop, y0 = c(1,1),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

We do in fact see the four equilibrium values that we calculated. Further, we can see the nullclines and since they do not intersect in more than four points, we conclude that we have found all of the equilibrium values.

Linear stability analysis

In general we have that

J(x,y)=(3−2x−2y−2x−y2−x−2y)

and thus

J(0,0)=(3002), which has τ=5, δ=6, and δ<14τ2.

J(0,2)=(−10−2−2), which has τ=−3, δ=2, and δ<14τ2.

J(3,0)=(−3−60−1), which has τ=−4, δ=3, and δ<14τ2.

J(1,1)=(−1−2−1−1), which has τ=−2 and δ=−1.

Thus, using the trace-determinant plane implies that the results of our linear stability analysis are:

(0,0) is an unstable node,

(0,2) is a stable node,

(3,0) is a stable node, and

(1,1) is a saddle.

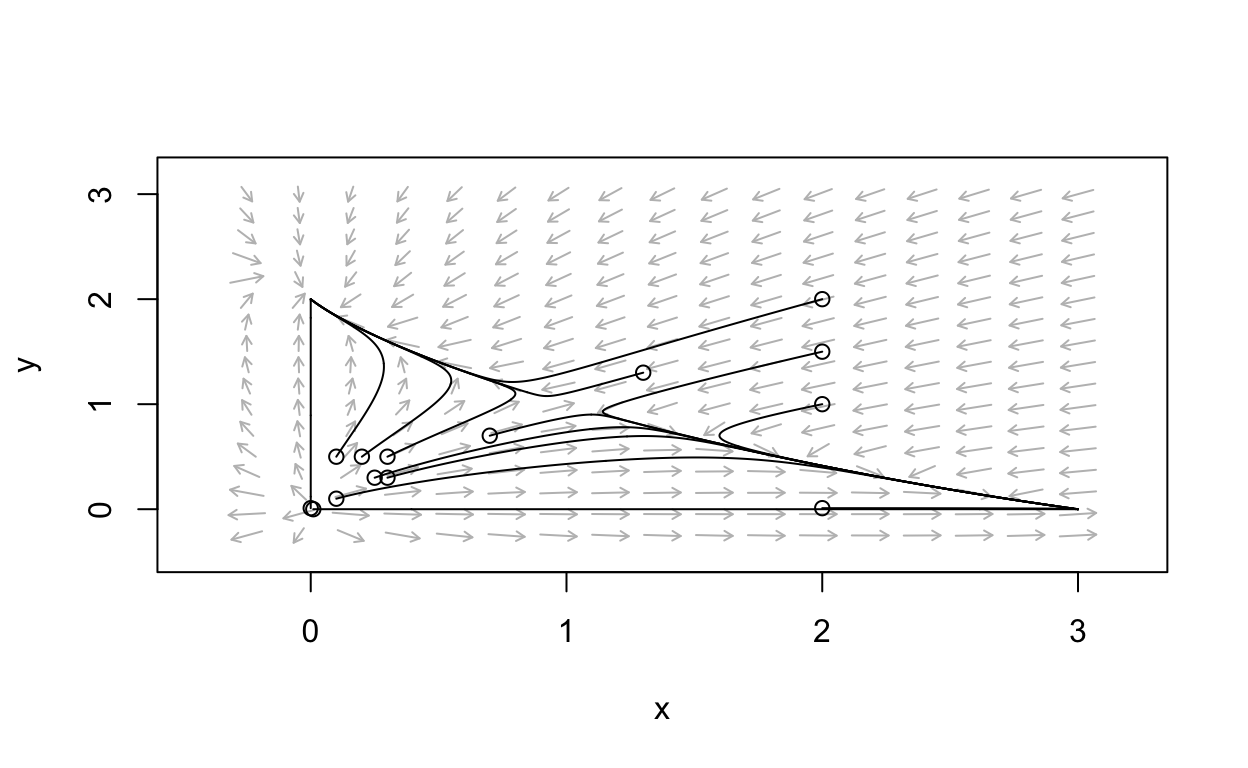

Phase portrait

We can easily obtain the phase portrait for the system

dxdt=x(3−x−2y)dydt=y(2−x−y)

using phaseR:

Conclusions

For the model system,

dxdt=x(3−x−2y)dydt=y(2−x−y)

An obvious question is, are there competition models in which there is a robust co-existence equilibrium? Consideration of this question is taken up in the next section.

A More General Competition Model

This section follows section 2.5 from (Britton 2003). A mathematical model for intraspecific competition is

dudt=r1u(1−u+αvK1)dvdt=r2v(1−v+βuK2)

where u and v are the populations of two species in competition. The parameters α and β are so-called competition coefficients.

Non-dimensionalization

We begin our analysis by non-dimensionalizing the system using the scalings x=uK1, y=vK2, and τ=r1t.

Then,

dxdτ=dtdτdxdt=1r1ddtuK1=1r1K1(r1u(1−u+αvK1))=x(1−K1x+αK2yK1)=x(1−x−αK2K1y)

and

dydτ=dtdτdydt=1r1ddtvK2=1r1K2(r2v(1−v+βuK2))=r1r2y(1−K2y+βK1xK2)=r1r2y(1−y−βK1K2x)

dxdτ=x(1−x−ay)dydτ=cy(1−bx−y)

where a=αK2K1, b=βK1K2, and c=r1r2.

Equilibrium points

Our analysis proceeds by determining the equilibrium points for

dxdτ=x(1−x−ay)dydτ=cy(1−bx−y)

0=x(1−x−ay)0=cy(1−bx−y)

Linear stability analysis

We want to determine if there are any conditions in which the coexistence steady-state (1−a1−ab,1−b1−ab) is stable. Generically, we have

J(x,y)=(1−2x−ay−ax−bcyc(1−bx−2y))

J(x∗,y∗)=J(1−a1−ab,1−b1−ab)=(−1−a1−ab−a1−a1−ab−bc1−b1−ab−c1−b1−ab)

tr(J(x∗,y∗))=−1−a1−ab−c1−b1−ab<0

det(J(x∗,y∗))=c(1−a)(1−b)(1−ab)2−abc(1−a)(1−b)(1−ab)2=c(1−a)(1−b)(1−ab)2(1−ab)

This will be positive if a<1 and b<1. Thus,

The coexistence steady-state exists and is stable if a<1 and b<1.

What does this mean in the context of the original model

dudt=r1u(1−u+αvK1)dvdt=r2v(1−v+βuK2)

Recall that a=αK2K1 and b=βK1K2. Notice that if a<1 and b<1, then

1>ab=αK2K1βK1K2=αβ.

Thus, when we have a stable coexistence steady-state we have αβ<1.

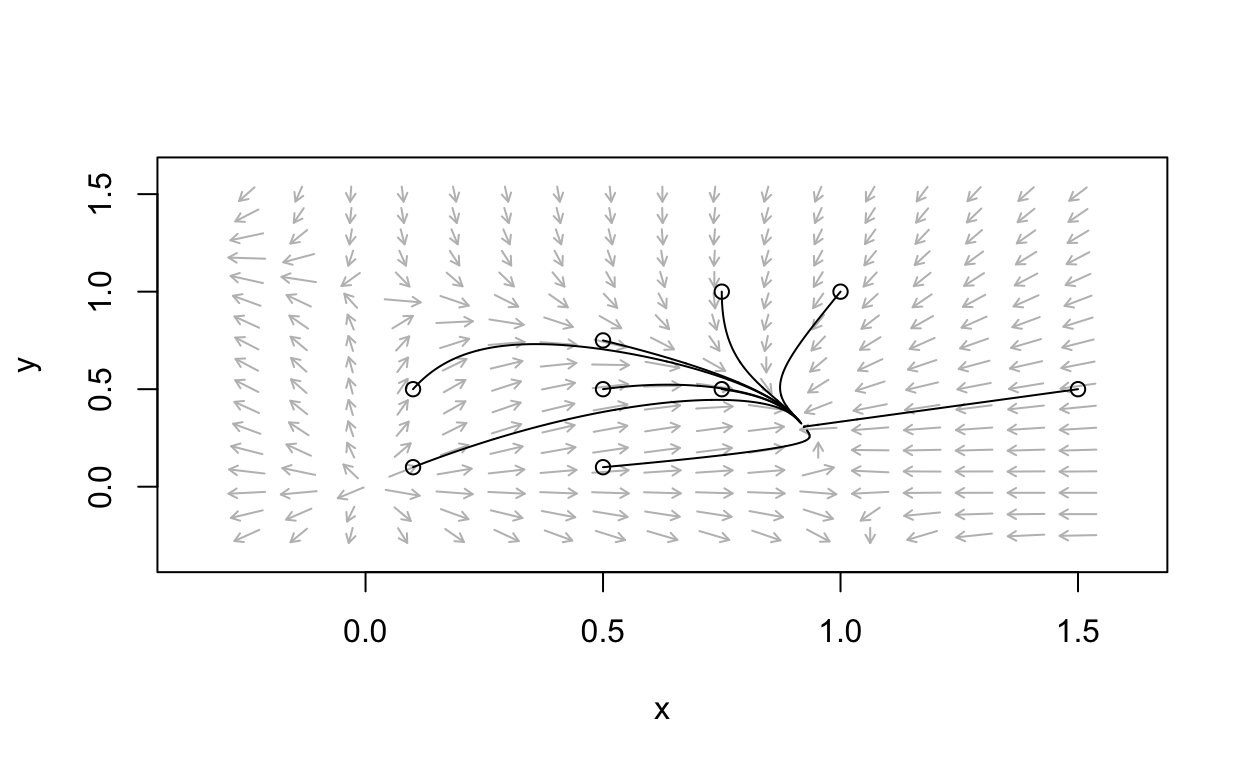

Example phase portrait

Here is an example phase portrait for a system of the form

dxdτ=x(1−x−ay)dydτ=cy(1−bx−y)

with a<1 and b<1.

Show code

nonlinear_example <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[1]*(1-state[1]-a*state[2])

dy <- c*state[2]*(1-b*state[1]-state[2])

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.25, 1.5),

ylim = c(-0.25, 1.5),

parameters = c(a=0.25,b=0.75,c=1.0),

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(0.1,0.1,0.5,0.1,0.1,0.5,0.5,0.5,

0.5,0.75,0.75,0.5,1.0,1.0,0.75,1.0,1.5,0.5),9,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(nonlinear_example,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 10),

parameters = c(a=0.25,b=0.75,c=1.0),add=TRUE)

It is clear that there is a stable equilibrium point with both components being positive values.

Conclusions

We have derived a condition for the existence of a stable coexistence steady-state. There is a further consequence of this analysis. Generally, two species with populations that obey

dudt=r1u(1−u+αvK1)dvdt=r2v(1−v+βuK2)

occupy the same ecological niche if αβ=1. If they coexist, then αβ<1. Therefore, competitors can not occupy the same ecological niche. This is a proof of the so-called principle of competitive exclusion.

Chemostat Model

For our final example, consider the chemostat model with non-dimensional form

dxdτ=a1y1+yx−xdydτ=−y1+yx−y+a2

Here, a1 and a2 are positive constants. The following analysis roughly follows that found in section 4.10 of (Edelstein-Keshet 2005).

Equilibrium points

Equilibrium points are determined by solutions to the system

0=a1y1+yx−x=x(a1y1+y−1)0=−y1+yx−y+a2

- (x∗,y∗)=(0,a2).

On the other have, if a1y1+y−1=0, then y=1a1−1. Solving the second equation for x gives

x=1+yy(a2−y)=1+1a1−11a1−1(a2−1a1−1)=(a1−1+1)(a2−1a1−1)=a1(a2(a1−1)−1a1−1)

- (x∗,y∗)=(a1(a2(a1−1)−1a1−1),1a1−1)

In the context of the biological system, only non-negative equilibrium values are relevant. Therefore, we only consider the second equilibrium whenever

a1>1, and

a2(a1−1)>1

Linear stability analysis

Let’s consider the linearization of the chemostat model at the equilibrium points. First, note that

J(x,y)=(a1y1+y−1a1x1(1+y)2−y1+y−x1(1+y)2−1)

y1+y=1a1

and

1(1+y)2=(a1−1a1)2

Therefore,

J(a1(a2(a1−1)−1a1−1),1a1−1)=(0(a1−1)(a2(a1−1)−1)−1a1−(a2(a1−1)−1)(a1−1a1)−1)

Now, this matrix has

trace τ=−(a2(a1−1)−1)(a1−1a1)−1<0, and

determinant δ=(a1−1)(a2(a1−1)−1)a1>0

from which we can conclude that (a1(a2(a1−1)−1a1−1),1a1−1) is a stable equilibrium (provided it exists as a positive equilibrium).

Finally, define A=(a1−1)(a2(a1−1)−1)a1, then we can write τ=−A−1 and δ=A, then

τ2−4δ=(A+1)2−4A=A2+2A+1−4A=A2−2A+1=(A−1)2>0

from which we conclude that (a1(a2(a1−1)−1a1−1),1a1−1) is a stable node.

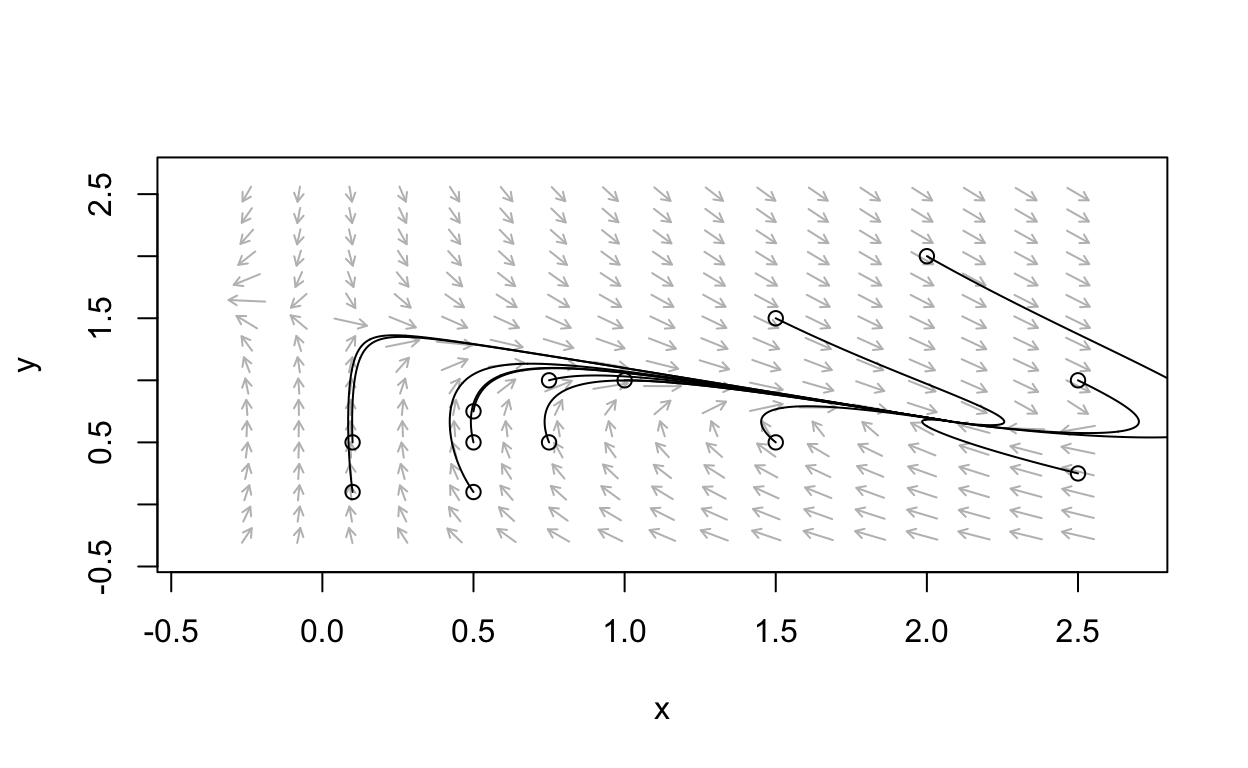

Example phase portrait

Show code

chemostat_example <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[1]*(a1*state[2]/(1+state[2]) - 1)

dy <- -state[1]*state[2]/(1+state[2]) - state[2] + a2

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(chemostat_example ,

xlim = c(-0.25, 2.5),

ylim = c(-0.25, 2.5),

parameters = c(a1=2.5,a2=1.5),

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(0.1,0.1,0.5,0.1,0.1,0.5,0.5,0.5,

0.5,0.75,0.75,0.5,1.0,1.0,0.75,

1.0,1.5,0.5,2.5,1.0,2.0,2.0,2.5,0.25,1.5,1.5),13,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(chemostat_example ,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 10),

parameters = c(a1=2.5,a2=1.5),add=TRUE)

We see that there is in fact an equilibrium point that is a stable node.

Conclusions

We have shown that there are conditions that result in long-term positive values for both a bacteria cell population and nutrient concentration. These are a1>1 and a2(a1−1)>1. Recall that in our non-dimensionalization we determined

a1=KmaxVF

and

a2=C0kn

Thus, we must have

Kmax<FV

and

FVknKmax−FV<C0

in order to get a stable positive steady-state solution to the chemostat model.