Goals

After reading this section of notes, you should

be able to conduct a linear stability analysis for a nonlinear autonomous system,

know how to use

phaseRto obtain phase-portraits for two-dimensional nonlinear systems, andknow how to compute numerical solutions for initial value problems for nonlinear systems using

deSolve.

Background

Previously, we have reviewed mathematical techniques for the analysis of one-dimensional autonomous systems and linear systems. In this section, we consider the analogous techniques for nonlinear autonomous systems of the form

ddtx=F(x)

where x∈Rn and F:Rn→Rn. Such a system is sometimes called a nonlinear vector field.

We have already encountered some nonlinear autonomous systems as mathematical models. For example, the predator-prey model, SIR model, and chemostat model are all nonlinear autonomous systems.

Equilibria for Nonlinear Systems

If ddtx=F(x) is a nonlinear autonomous system, then we say that a vector x∗ is an equilibrium if it satisfies F(x∗)=0. A typical problem is to determine the stability properties of equilibria for nonlinear systems. In general this can be a difficult problem. However, in some cases when can use linearization to say something about the stability of equilibria. We begin by reviewing this technique in the two-dimensional case.

Two-Dimensional Case

We can write a two-dimensional nonlinear autonomous system as

dxdt=f(x,y)dydt=g(x,y)

Then an equilibrium is a point (x∗,y∗) satisfying the simultaneous system

f(x∗,y∗)=0g(x∗,y∗)=0

For example, the system

dxdt=2x−3xydydt=xy−4y

has two equilibria, (0,0) and (4,32).

If (x∗,y∗) is an equilibrium point for a two-dimensional nonlinear autonomous system, then we call the matrix

J(x∗,y∗)=(fx(x∗,y∗)fy(x∗,y∗)gx(x∗,y∗)gy(x∗,y∗))

the linearization of the system at the equilibrium (x∗,y∗). It turns out that in some cases, the linearization can be used to determine the stability of the equilibrium (x∗,y∗). Specifically, if the eigenvalues of J(x∗,y∗) have nonzero real part, then near the equilibrium, the system behaves exactly as the corresponding linear system ddtx=J(x∗,y∗)x behaves. This is a result known as the Hartman-Grobman theorem.

Consider again the example system

dxdt=2x−3xydydt=xy−4y

which possesses equilibria (0,0) and (4,32). Then

J(0,0)=(200−4), J(4,32)=(0−12320)

Phase-Portaits

It is possible to study two-dimensional autonomous systems geometrically analogous to what we did with one-dimesional autonomous systems. But in this case, we draw a phase-plane instead of a phase-line. To understand this, first note that a solution to the system

dxdt=f(x,y)dydt=g(x,y)

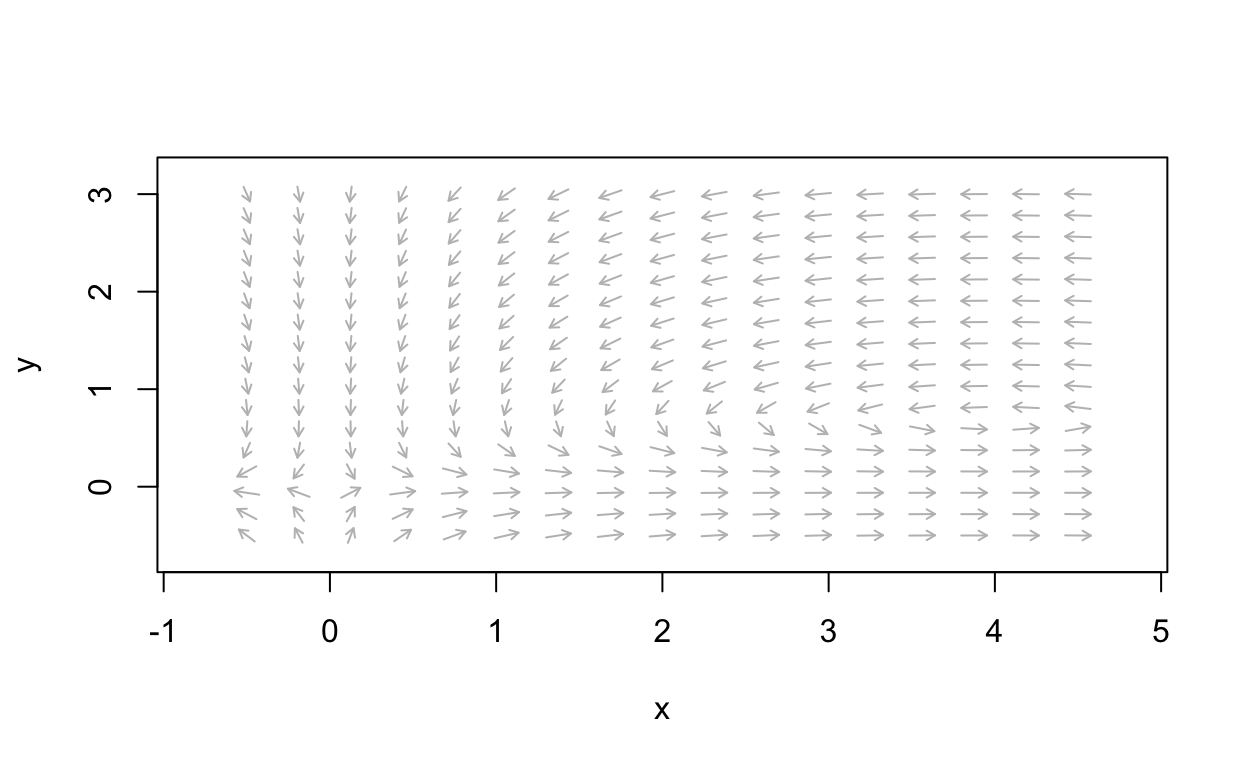

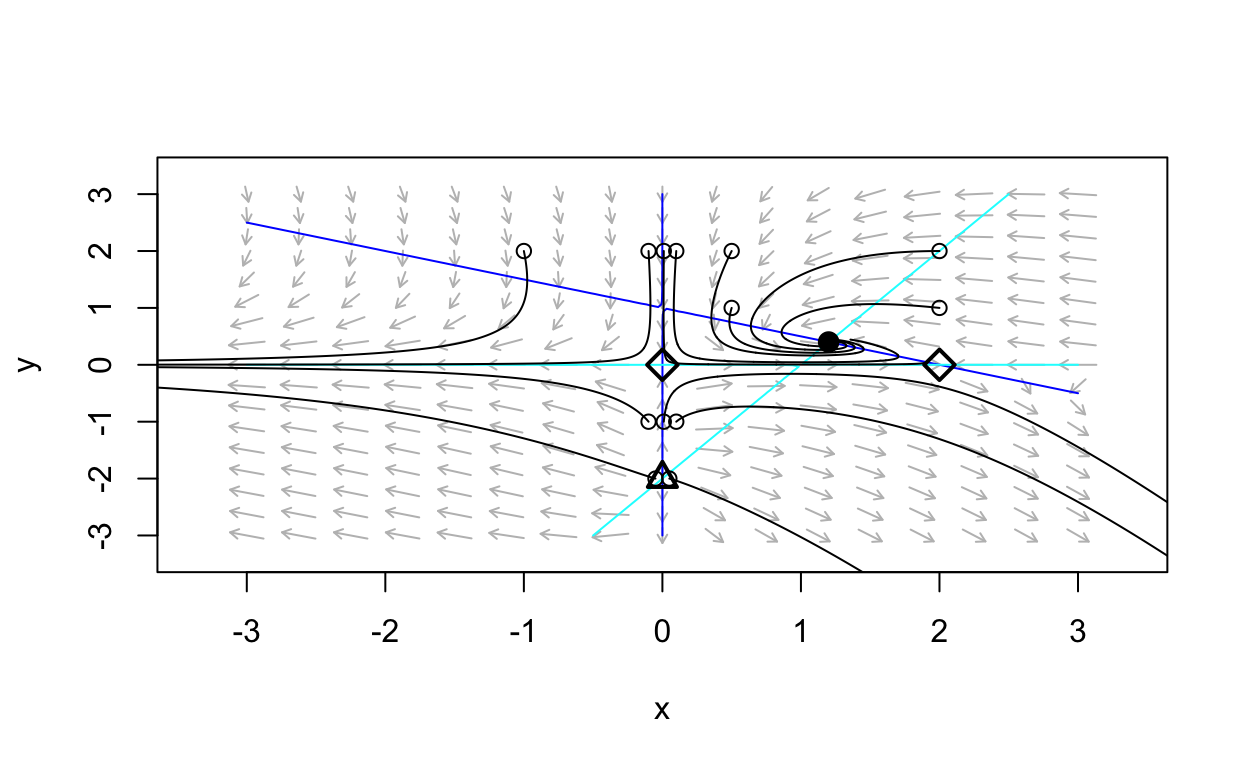

For example, the following plot shows the vector field for

dxdt=2x−3xydydt=xy−4yShow code

nonlinear_example <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- 2*state[1] - 3*state[1]*state[2]

dy <- state[1]*state[2] - 4*state[2]

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.5, 4.5),

ylim = c(-0.5, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

It is easy to see that there is a saddle point at (0,0). Furthermore, from the vector field

it appears that there are rotations around (4,32) which suggests either a

sprial or perhaps a nonlinear center. We will explore this further soon.

First, reacll that if dxdt=f(x,y)dydt=g(x,y)

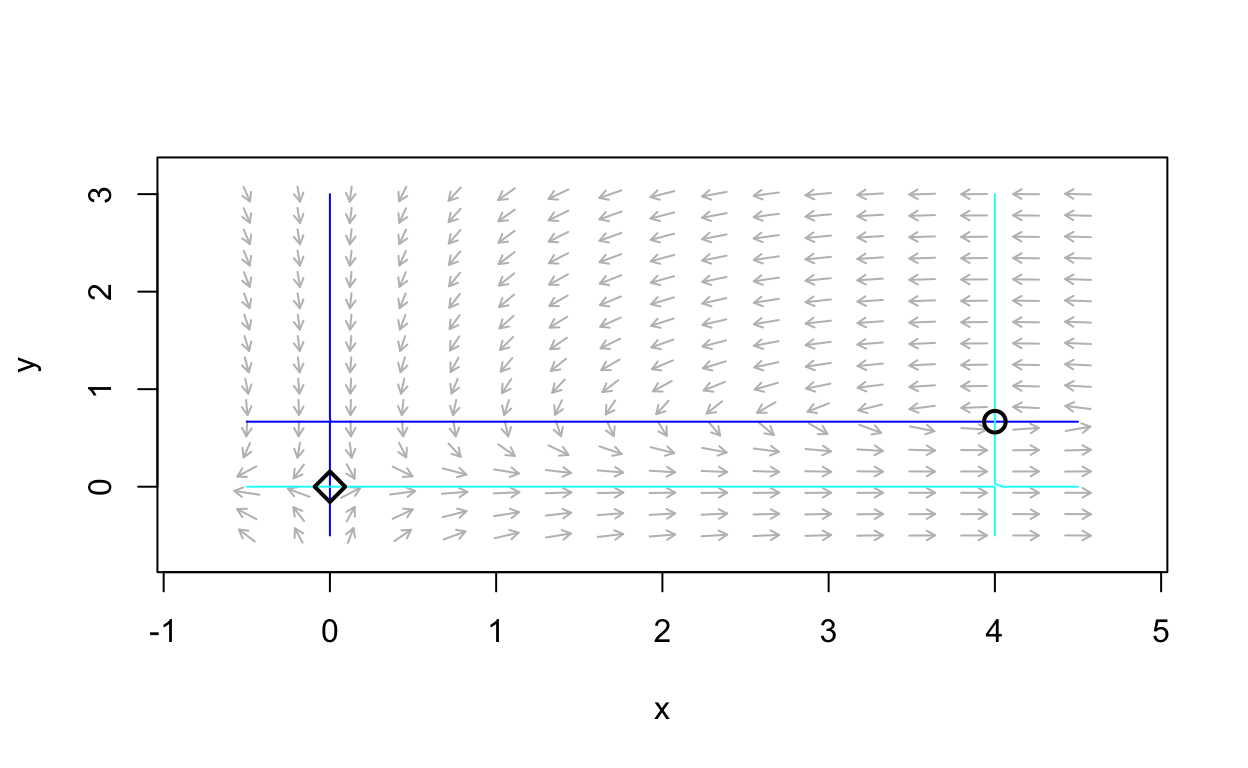

is a nonlinear system, the setting each component of the vector field to zero determines curves. Thus there are f(x,y)=0 curves and g(x,y)=0 curves. Such curves are called nullclines. This is due to the fact that along a f(x,y)=0 curve, we have that dxdt=0 and hence there is no change in the x direction. On the other hand, along a g(x,y)=0 curve, we have that dydt=0 and hence there is no change in the y direction. Note that equilibria points are exactly intersectoin points of distinct nullclines. The following plot shows the nullclines for the example system

dxdt=2x−3xydydt=xy−4y

Show code

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.5, 4.5),

ylim = c(-0.5, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.5, 4.5),

ylim = c(-0.5, 3),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(nonlinear_example, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq2 <- findEquilibrium(nonlinear_example, y0 = c(4,3/2),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

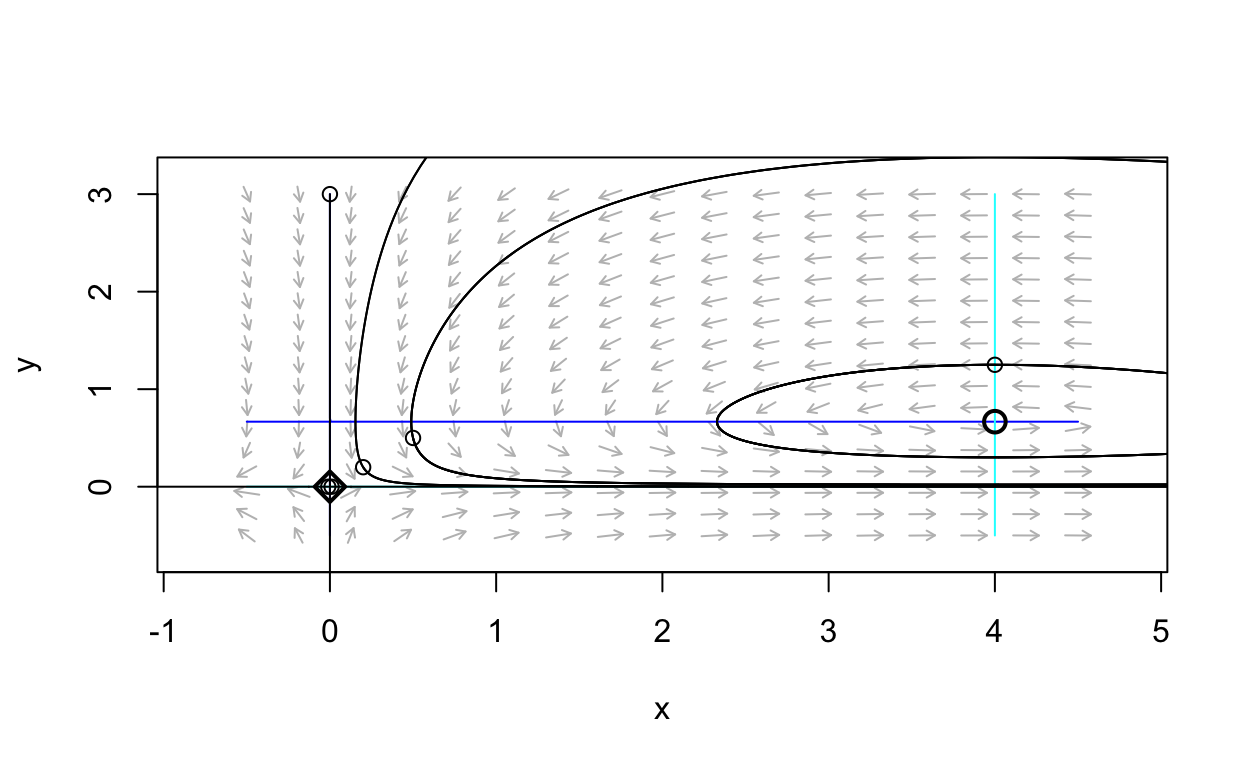

We can see the equilibrium points at the intersection of distinct nullclines. Let’s plot several trajectories to obtain a phase-portrait.

Show code

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.5, 4.5),

ylim = c(-0.5, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(nonlinear_example,

xlim = c(-0.5, 4.5),

ylim = c(-0.5, 3),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(nonlinear_example, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq2 <- findEquilibrium(nonlinear_example, y0 = c(4,3/2),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(0.2,0.2,0.5,0.5,0,3,0,-1,0.01,0,-0.01,0,4,1.25),7,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(nonlinear_example,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 10),

parameters = NULL,add=TRUE)

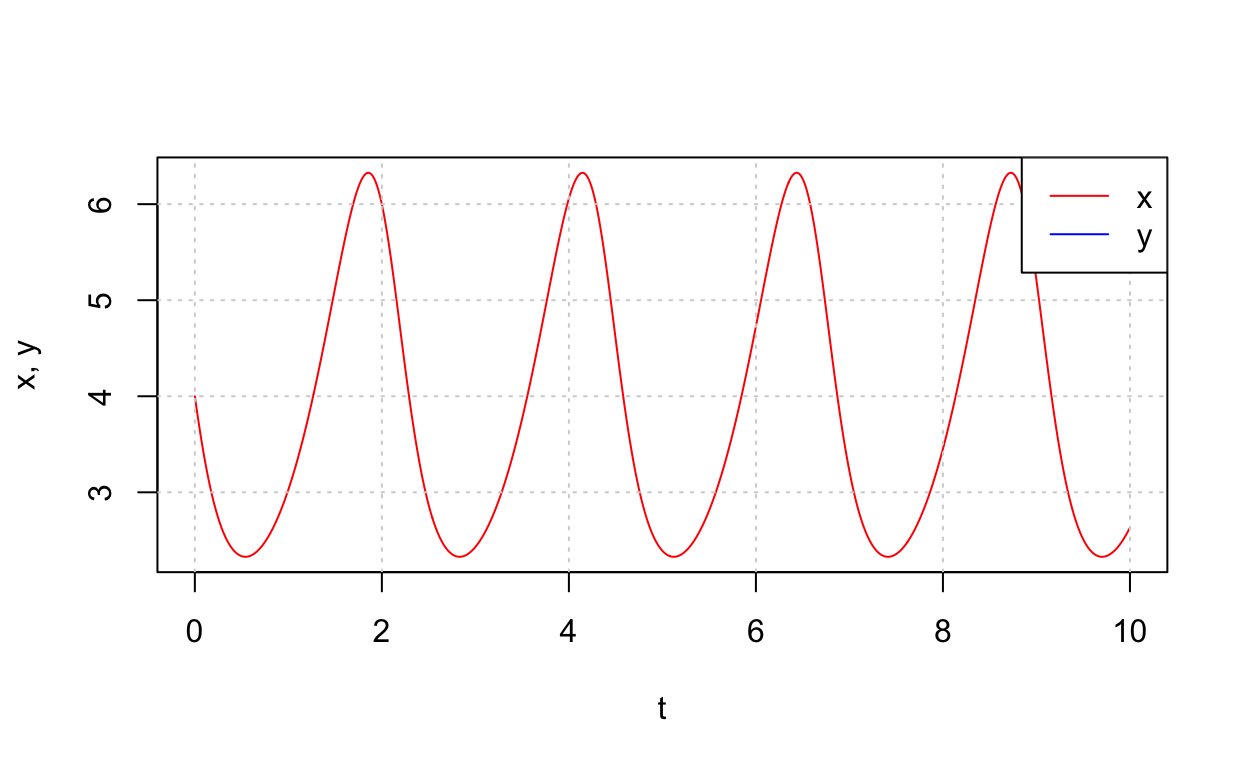

Notice that this system has trajectories that are closed curves in the plane. Thus, this system possesses periodic solutions. To confirm this, let’s plot the time-series for one of the trajectories that appears to correspond to a periodic solution. Namely, let’s plot the solution corresponding to initical condition (4,1.25).

Show code

num_sol <- numericalSolution(nonlinear_example,y0=c(4,1.25),tlim=c(0,10))

We will return to the topic of periodic solutions to nonlinear systems later. For now, note that linearization cannot typically be used to detect the existence of periodic solutions.

A Gallery of Two-Dimensional Systems

What follows is a sequence of examples of using phaseR

to produce a phase portrait for a two-dimensional nonlinear autonomous

system. As an exercise, you should attempt to determine the equilibria

and their stability properties for each system.

Show code

gallery_example_1 <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[1]*(1 - 0.5*state[1] - state[2])

dy <- state[2]*(state[1] - 1 - 0.5*state[2])

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(gallery_example_1,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(gallery_example_1,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_1, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq2 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_1, y0 = c(2,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq3 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_1, y0 = c(0,-2),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq4 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_1, y0 = c(6/5,2/5),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(-0.1,-1,-0.1,2,

0.01,-1,0.01,2,

0.1,-1,0.1,2,-0.05,-2,

0.5,1,0.05,-2,0.5,2,

2,1,2,2,-1,2),13,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(gallery_example_1,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 10),

parameters = NULL,add=TRUE)

Show code

gallery_example_2 <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[2]

dy <- state[1]*(1 - state[1]^2) + state[2]

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(gallery_example_2,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(gallery_example_2,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_2, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq2 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_2, y0 = c(1,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

eq3 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_2, y0 = c(-1,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(0.01,0.01,0.01,-0.01,-0.01,0.01,-0.01,-0.01,

-0.5,0.0,0.5,0.0,

-1,-0.1,-1,0.1,1,-0.1,1,0.1),10,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(gallery_example_2,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 10),

parameters = NULL,add=TRUE)

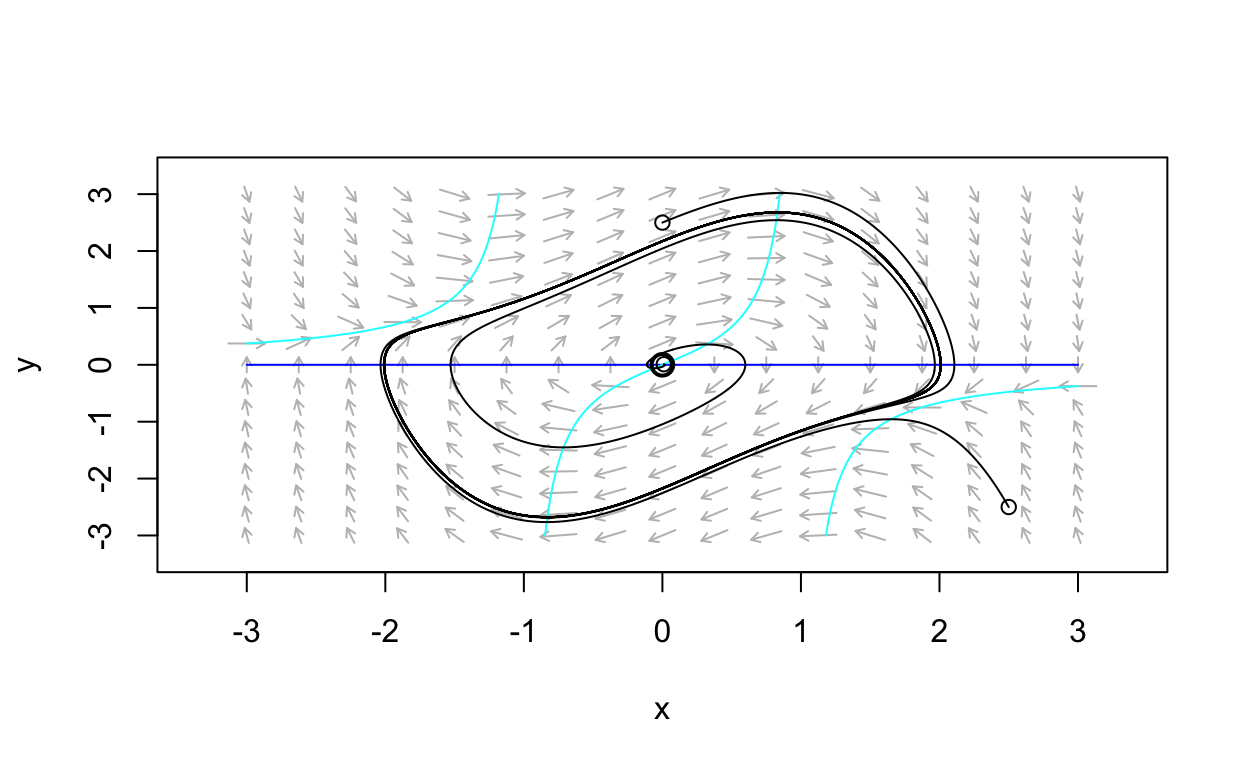

Show code

gallery_example_3 <- function(t,state,parameters){

with(as.list(c(state,parameters)),{

dx <- state[2]

dy <- -state[1] + (1 - state[1]^2) * state[2]

list(c(dx,dy))

})

}

nonlinear_flowfield <- flowField(gallery_example_3,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

parameters = NULL,

points = 17,

add = FALSE)

nonlinear_nullclines <- nullclines(gallery_example_3,

xlim = c(-3, 3),

ylim = c(-3, 3),

points=100,add.legend=FALSE)

eq1 <- findEquilibrium(gallery_example_3, y0 = c(0,0),

plot.it = TRUE,summary=FALSE)

state <- matrix(c(0.01,0.01,0,2.5,2.5,-2.5),3,2,byrow = TRUE)

nonlinear_trajs <- trajectory(gallery_example_3,

y0 = state,

tlim = c(0, 50),

parameters = NULL,add=TRUE)

Higher Dimensional Systems

As the dimension of a nonlinear system increases so does the

difficulty in analyzing the equilibria and their stability properties.

Once the dimension is three or greater, geometric analysis ranges from

very difficult to impossible. Thus, in Topics in Biomathematics

we will resign ourselves to handling larger nonlinear systems with

numerical computing using the deSolve package. We

illustrate this with an example.

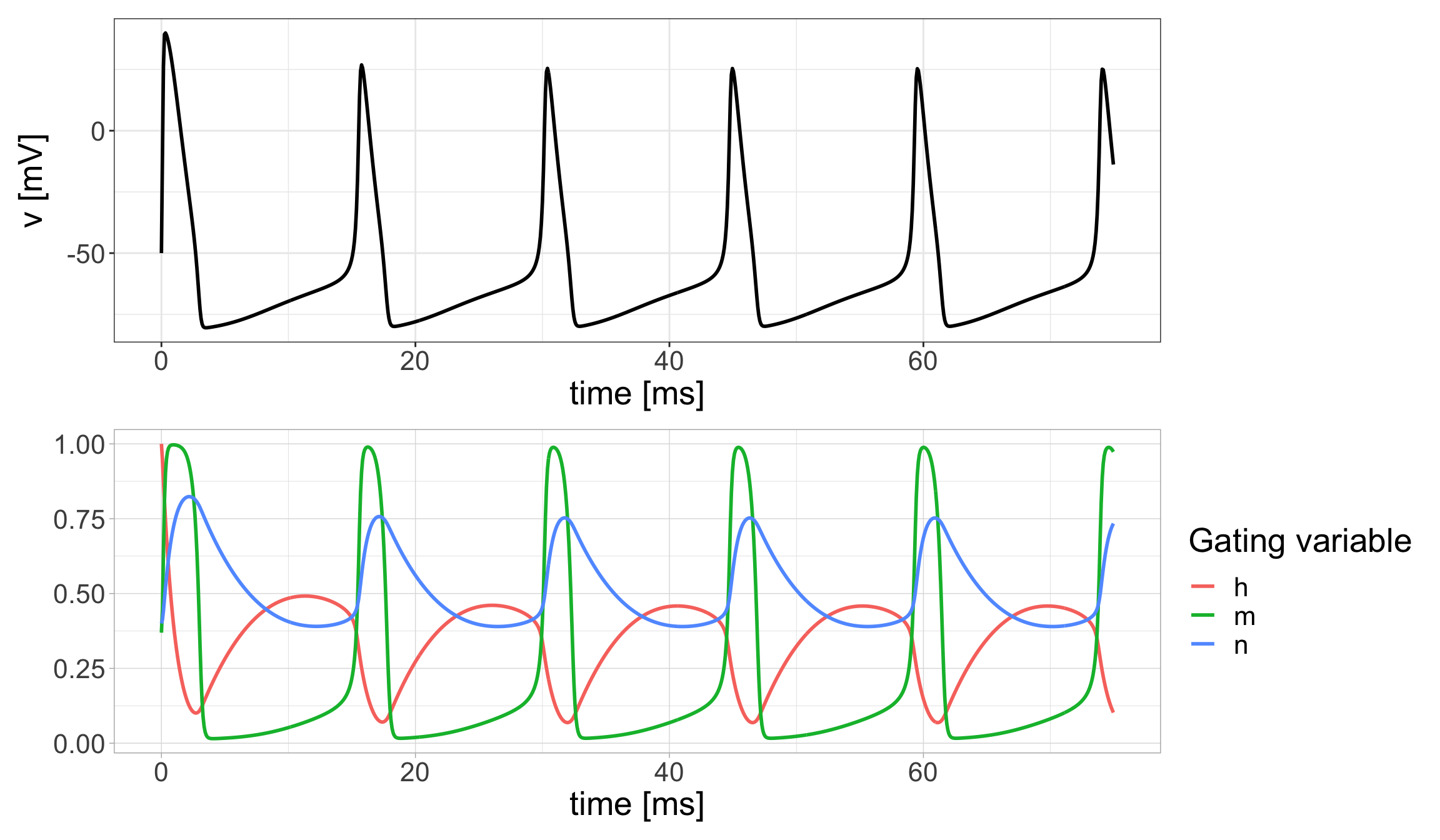

Hodgkin-Huxley Model

Neuronal dynamics is concerned with the dynamical behavior of components of the nervous system and forms the basis for computational neuroscience. The starting point for this field of research is the Hodgkin-Huxley model for the neuron action potential. We will discuss this model in detail later. For now, we write down the equations mostly to note that the model is made up of a system of four nonlinear differential equations:

Cddtv=gnam3h(vna−v)+gkn4(vk−v)+gl(vl−v)+iextddth=hinf−hτhddtm=minf−mτmddtn=ninf−nτndeSolve.

Show code

source("./R/gatingVariables.R")

# parameters

parameters <- list(C=1,gk=36,gna=120,gl=0.3,vk=-82,vna=45,vl=-59,iext=10)

# initial conditions

v0 <- -50

m0 <- alpha_m(v0)/(alpha_m(v0)+beta_m(v0));

yini <- c(v=v0, h=1, m=m0, n=0.4)

t_initial <- 0

t_final <- 75

times <- seq(from = t_initial, to = t_final, by = 0.08)

# define function to be in the format that `ode` uses

HH <- function (t, y, parameters) {

with(as.list(c(y,parameters)),{

# variables

v <- y[1]

h <- y[2]

m <- y[3]

n <- y[4]

# functional forms

h_inf <- alpha_h(v)/(alpha_h(v) + beta_h(v))

m_inf <- alpha_m(v)/(alpha_m(v) + beta_m(v))

n_inf <- alpha_n(v)/(alpha_n(v) + beta_n(v))

tau_h <- 1/(alpha_h(v) + beta_h(v))

tau_m <- 1/(alpha_m(v) + beta_m(v))

tau_n <- 1/(alpha_n(v) + beta_n(v))

dv <- (gna*m^3*h*(vna - v) + gk*n^4*(vk - v) + gl*(vl - v) + iext)/C

dh <- (h_inf - h)/tau_h

dm <- (m_inf - m)/tau_m

dn <- (n_inf - n)/tau_n

return(list(c(dv, dh, dm, dn)))

})

}

out <- ode(y = yini, times = times, func = HH,

parms = parameters,method = "ode45")

In order to run the code above, you need an R script

gatingVariables.R which is available here.

Let’s plot our results:

Show code

HHsol <- data.frame(t=out[,"time"],v=out[,"v"],h=out[,"h"],m=out[,"m"],n=out[,"n"])

p1 <- HHsol %>%

ggplot(aes(x = t, y = v)) +

geom_line(aes(x = t, y = v),lwd=1) +

labs(x="time [ms]",y = "v [mV]") +

theme_bw() + theme(text=element_text(size=20))

p2 <- HHsol %>%

pivot_longer(-c(t,v),names_to="Variable", values_to="Value") %>%

ggplot(aes(x = t, y = Value, color = Variable)) +

geom_line(aes(x = t, y = Value),lwd=1) +

labs(x="time [ms]",y = " ") +

guides(color=guide_legend(title="Gating variable")) + theme(text=element_text(size=20))

(p1 / p2)

A distinct feature of the dynamics is the periodic nonlinear oscillations. We will have more to say about this later. From now on, anytime you encounter a model that is made up of large system of equations in Topics in Biomathematics, you should try to explore the model behavior by producing numerical solutions as we have done here with the Hodgkin-Huxley model.

Further Reading

For more information on the dynamics of nonlinear systems, we recommend the following sources (Allen 2007), (Barnes and Fulford 2015), (Britton 2003), (de Vries et al. 2006), (Edelstein-Keshet 2005), (Hirsch and Smale 1974), (Jones, Plank, and Sleeman 2010), (Strogatz 2015).

A good reference for the Hodgkin-Huxley model is (Börgers 2017).